A recent headline in the Washington Post stated,

Writing to the future is one of the most powerful climate actions you can take

Social scientists say writing a letter to loved ones in the future can overcome a critical climate problem: inaction.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2025/04/29/climate-action-letter-to-the-future/

Apparently, having people write letters to their future children is one of the best ways to motivate people to take stock and become more active. Michael J. Coren writes:

Can writing letters like these really change people’s behavior? Some studies suggest it may be one of the most powerful ways to inspire support for climate action—and among the few to work across the political divide.

This past week, I wrote a letter to my own children, the youngest of whom will be my age by 2070. It forced me to confront what no study or trend line had before: My children will never know the world I grew up in. From the shores to the mountains, many of the places near our home in San Francisco will be transformed. Globally, an estimated 30 percent of the population will endure “near-unliveable” temperatures that rival the hottest parts of the Sahara.

Yet writing the letter was not demotivating. It was clarifying. When the time came, I wanted to be able to answer their question: What did you do?

So here is an excerpt from our “letter to the future,” addressed to our granddaughter Amira, then only a few months old.

Saturday, April 6, 2024

Our Dear Amira:

On our 37th Wedding Anniversary (April 5th), your grandmother Victoria and I decided to write something for you to read later on (should both you and the Internet survive), about how things are in the world today, as best we’re able to see them.

We humans have monumentally screwed things up. As a species we are now in overshoot, and arguably in the midst of ecological collapse. There is an increasingly narrow pathway to avoid near-term human and wildlife extinction. At the same time, we ourselves are captives of the very system that is leading us to committing ecocide. We live in a small suburban home, drive a fourteen-year-old hybrid, and do very little traveling. But even our modest lifestyle is unsustainable.by any realistic measure. We get our food from the grocery store. Thanks to Medicare and our secondary insurance our health care is pretty much taken care of and we have access to yjr latest advances in modern medicine. When the weather permits, in spring and summer, we spend half our time gardening, and the other have sitting in front of a computer. Is there a way to have global networks survive the collapse?

Historically, as civilizations break down, much of their culture and technology is lost. Life becomes more primitive, and more just about day-to-day survival. People will need to depend on each other in local communities. We’ll need to supply our food, clothing, and shelter from our immediate neighbors, rather than from the institutions of the consumer industrial economy. We’ll need to invest in restoring the planet rather than plundering it.

As individuals, we are largely powerless to do anything about this. It is as if humans were destined to fail in just this way. Overshoot is a common phenomenon in the ecological world, but it is mostly self-correcting. That is, animals who exceed their food supply run into a natural barrier to further expansion; and in the wild their numbers are kept in check by predators. Humans have what seems like a natural tendency to avoid starvation or get eaten by other animals, so to the extent that they have been able to expand their food supply they have easily grown beyond what could be maintained by hunting and gathering or subsistence agriculture. And with explosive population growth, humans decided to try to overcome other natural barriers as well. With more than eight billion people today, the world has overshot several limiting factors in ways that cannot be sustained.

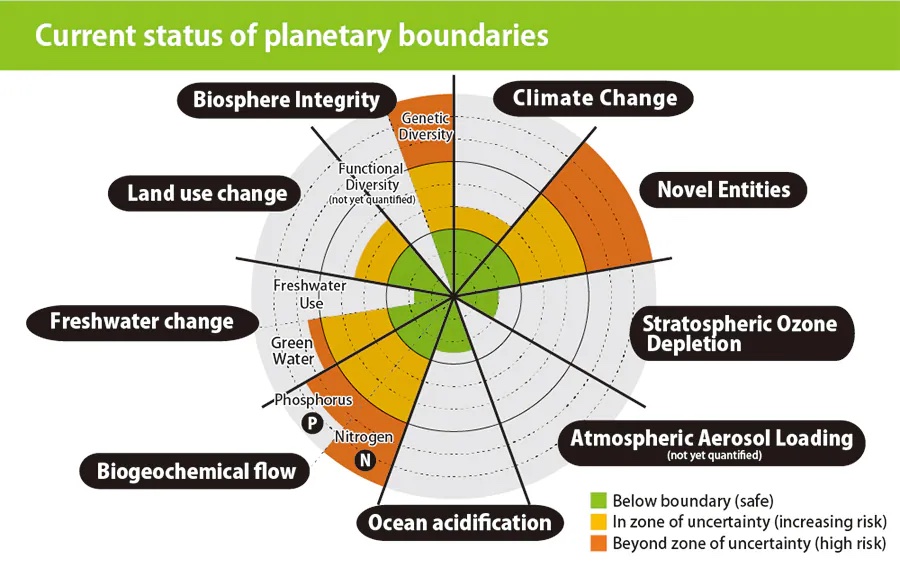

A popular way of describing this is the framework of planetary boundaries developed by the Stockholm Resilience Center. The following diagram is current as of 2022, showing six of the boundaries as having been crossed, the most significant being Biosphere Integrity, Biogeochemical Flows, and Novel Entities. Other important ones are Freshwater, Land Use, and Climate Change. With these boundaries breached, the future of our planet looks bleak.

This image is taken from https://social-innovation.hitachi/en/article/planetary-boundaries/, based on an interview with Dr. Kazuhiko Takeuchi, President of the Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES). Notably, it is published by Hitachi, one of the many companies that have contributed to worsening the polycrisis. This is what we now call the convergence of crises, any one of which could spell disaster for the planet.

This image is taken from https://social-innovation.hitachi/en/article/planetary-boundaries/, based on an interview with Dr. Kazuhiko Takeuchi, President of the Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES). Notably, it is published by Hitachi, one of the many companies that have contributed to worsening the polycrisis. This is what we now call the convergence of crises, any one of which could spell disaster for the planet.

Consider climate change. The climate will be very different in your lifetime. We’re just beginning to experience global warming — the temperature average just reached the 1.5°C that had been set by the Paris Climate Agreement. And the use of fossil fuels continues to increase, so it’s unlikely that we’ll reach the governmental target of 50-55% reduction in fossil fuel use by 2030. In Storms of My Grandchildren, James Hansen, NASA’s foremost climate scientist, warned Congress that we needed to change course back in the 1980s. In 2009, when he released the book, he was explicit about “the coming climate catastrophe and our last chance to save humanity.” He writes,

The urgency of the situation crystallized only in the last few years.We now have clear evidence of the crisis, provided by increasingly detailed information about how Earth responded to perturbing forces during its history (very sensitively, with some lag caused by the inertia of massive oceans) and by observations of changes that are beginning to occur around the globe in response to ongoing climate change. The startling conclusion is that continued exploitation of all fossil fuels on Earth threatens not only the other millions of species on the planet but also the survival of humanity itself—and the timetable is shorter than we thought.

Of course we’re not telling you anything that you will not already know first-hand; we just wanted to explain the state of our own knowledge in 2024, and why we’re so concerned. And the climate crisis may not be the worst thing we have to consider. It is likely to unfold over the next several decades, while the ecological collapse may occur much sooner than that.

Paradoxically, ecological collapse may have a beneficial effect on the climate crisis. Just as the pandemic led to a global reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, any physical or social breakdown that effectively interrupts global capitalism, that leads to greater localization, and reduces the activity of the extractive economy, will diminish our societal pressure on the environment. Of course, this will be accompanied by different kinds of disruption that may be equally unpleasant for our species. A breakdown in the global food supply chain will likely have devastating effects on poorer populations, and maybe even on wealthier ones — we forget how quickly whole societies can descend into chaos and deprivation, as happened during the Great Depression. A depression triggered by a sudden loss of confidence in the markets, or by overexploitation of resources, or by wrongheaded governmental policies, can wipe out the wealth of whole classes of individuals.

A little more than a year later (May 2025), this is what we are witnessing as the new Trump administration tries to take us backward from the climate-oriented policies of the Biden era. It’s not just that they are changing direction; it’s that they’re trying to eliminate climate science altogether. With the very visible assistance of Elon Musk, the Trump administration has dismissed almost all of the U.S. government’s climate scientists; cancelled millions of dollars of federal grants and contracts; and tried to remove the word “climate” from government websites.

In January I published a blog post (in DeadRiverJournal.org) pointing out the effort to suppress the idea of the social cost of carbon, calling it “logically deficient,” “poorly based in empirical science,” “politicized,” and “absent of a foundation in legislation”. It’s fine to critique the concept, but trying to deny its existence strikes us as madness. Ignoring it won’t make it go away. Or will it? Can we “unknow” what is already established science?

What’s remarkable is that asking people to write a letter to the future has a positive impact on them in the present. The Washington Post article notes, “Shrum asked nearly 2,000 people from all 50 states to write either an essay or letter to a family member in the future about the risks of climate change. A third control group wrote about their daily routines. Participants, who were paid, could then donate any amount from a potential $20 bonus to a tree-planting charity focused on global warming.

“The results, published in the peer-reviewed journal Climatic Change in 2021, and supported in follow-up experiments, showed that while writing about climate risk didn’t change anyone’s perception of climate risk, it did change their willingness to act on it. Donations among letter and essay writers increased 11 percent relative to the control group, a relatively large effect in social sciences.”

(This chapter is not “AI-assisted.”)